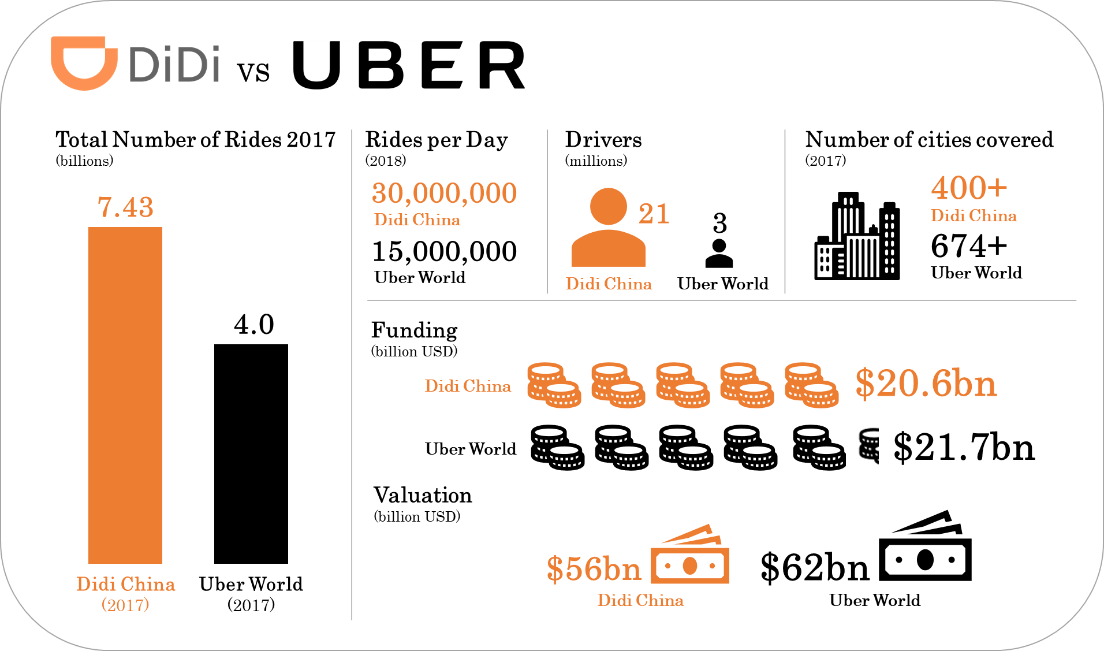

In 2013, Uber entered China. The ambitious CEO of Uber at the time, Travis Kalanick, was determined to win. Three years later, Uber China gave up. It sold its business to the local competitor DiDi in 2016 and left with a small market share.

While the Chinese government protectionism was somewhat to blame, Uber still made avoidable mistakes along the way that led to its failure.

Rocky Start

Uber first launched its service in China with credit-card as the only payment option. Most Chinese consumers, however, were not used to linking credit cards to digital services. They used either WeChat Pay or Alipay. With credit card as the only payment method, Uber prevented lots of Chinese mobile users from signing up the service.

In addition, Uber initially used Google Map as the third-party map provider, a service blocked by China's great fire wall. It took the company more than a year to partner up with Baidu, which agreed to provide Uber its mapping technology.

Copy and Paste

Uber had it right in U.S. It found that once a city reached a critical number of riders and drivers, customers were very likely to stick with the service. According to Uber, it only took 2.7 rides for someone to become a continuing customer. It was the magical number that worked in LA and San Francisco.

To copy the same success, Uber China went hard to hit the "right" number. To increase the supply and demand, it offered drivers and riders unreasonable incentives to onboard the service: lax background checks, generous driving bonuses, and free rides.

However, this brute, capitalistic growth strategy that worked in U.S. did not work so well overtime in China. It created backlashes. Taxi drivers accused Uber of stealing their jobs. The public criticized Uber for putting passengers at safety risk. Cities were angry.

By comparison, the competitor DiDi took a more measured, "Chinalistic" approach to penetrate the market. Firstly, DiDi connected riders with just licensed taxi drivers. Only after did it open its service to private drivers. Secondly, Didi built relationships with the government. It helped manage over 1,300 city traffic lights in partnership with city governments. Lastly, DiDi secured investment from tech powerhouses. It was the only company backed by all three tech Chinese giants, Tencent, Alibaba, and Baidu. Even Apple injected money into the company.

Didi was much better-positioned in the market. Uber was disadvantaged from Day 1.

Price-War

To compete with Didi, Uber waged a price war. On a typical week, it would drop $40-50 million US dollars per week on free rides and bonuses in China. It was not sustainable. Not only so, the free ride promotion program also created loopholes for scammers. Users would take fake rides, one acting as the driver, the other as the driver, splitting the profit. In one Chinese city, half of all rides were fraudulent. The summer of 2015, more than 30,000 fake rides were taken everyday in China. Uber burned cash like a car eating fuel. It was just a matter of time before Uber exhausted itself.

The Uber final days came in August, after China legalized the industry in response to crimes committed by ride-hailing drivers. The new rules required drivers to have 3 years of experience, and there could be no subsidies.

Days after the new regulation, Uber sold its business unit to DiDi and left with assets valued at 7 billions dollars. Given the fact that Uber spent just 2 billions in China, it still made a decent profit. So, was it a failure? Yes, but financially speaking, a profitable one.